In the world of accounting, depreciation is simply the way we spread out the cost of a big-ticket item, like a machine or a vehicle, over the time we expect to use it. Think of it as accounting for the slow, steady decline in an asset's value from wear and tear, age, or just becoming obsolete.

Understanding Depreciation as an Essential Accounting Concept

Let's make this real. Imagine a small bakery buys a new delivery van for $50,000. It wouldn't be accurate to write off that entire $50,000 as an expense in the very first month. Why not? Because that van is going to be delivering cakes and generating income for years to come.

Dumping the whole cost upfront would make month one look like a financial disaster and all the following years seem unusually profitable.

Depreciation fixes this. It lets us spread the van's cost across its expected lifespan, neatly aligning the expense with the revenue it helps bring in. This is a bedrock concept in accounting called the matching principle.

The Purpose and Importance of Depreciation

Here’s a common misconception: depreciation isn't about tracking an asset's real-time market value. The van’s Kelley Blue Book value might go up or down, but its value on the company’s books follows a consistent, planned-out schedule. The real goal is to give a true picture of the company's profitability and asset base on its financial reports.

Understanding this is crucial for anyone trying to read the story a company's finances are telling. For a closer look at where this story gets published, our guide on what are the financial statements is a great next step.

So, why is this so important?

- Accurate Profit Measurement: It lines up a piece of an asset’s cost with the revenue that asset helps generate. This gives you a much truer look at your net income.

- Realistic Asset Valuation: It gradually lowers an asset's value on the balance sheet, which shows it's being "used up" and prevents the company from looking like it's worth more than it really is.

- Tax Implications: Here's the best part for many businesses. Depreciation is a non-cash expense. It lowers your taxable income without you having to spend any actual money, which often means paying less in taxes.

By recording depreciation, a company creates a more faithful representation of its financial health, showing investors and lenders how its assets are being consumed to create value.

Key Terms You Need to Know

Before we dive into the calculations, let's get a handle on the basic vocabulary. These are the building blocks you'll need to understand how depreciation works in practice. Each one is a critical piece of the puzzle.

Here are the fundamental concepts you need to know to understand asset depreciation.

Quick Answer Key: Depreciation Terms

| Term | What It Means in Plain English |

|---|---|

| Depreciation | The process of spreading an asset's cost over the time it's used. |

| Asset Cost | The total price to buy and prepare an asset for use. |

| Useful Life | The estimated time an asset will be productive for the business. |

| Salvage Value | The asset's estimated resale or scrap value at the end of its life. |

| Book Value | The asset's cost minus all depreciation recorded so far. |

Once you have a solid grasp on these terms, you're ready to see how they all fit together in the different depreciation formulas.

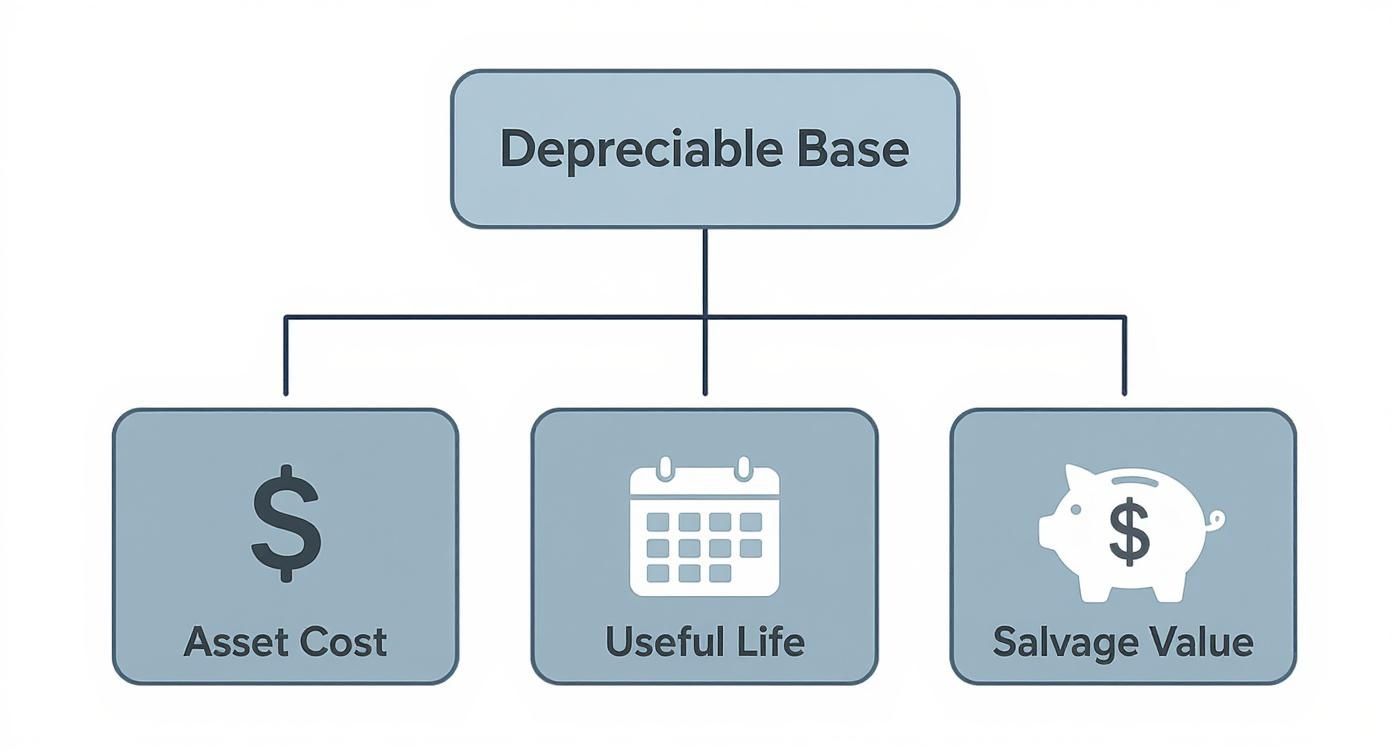

The Core Components of Depreciation Calculation

To figure out depreciation, you really only need three key pieces of information. Think of them as the building blocks for any depreciation calculation. Without them, you're just guessing. These three elements are the asset's total cost, its useful life, and its salvage value.

Getting these numbers right is crucial. It’s the foundation for every method, whether you're depreciating a single delivery van or an entire factory floor full of equipment. Let's dig into what each of these components really means.

Determining the Full Asset Cost

First up is the asset cost. This isn't just the sticker price. It’s the total cash you laid out to not only buy the asset but also get it up and running for its intended purpose. In accounting speak, this is the "capitalized cost"—the amount that goes onto your balance sheet as an asset.

Let’s say a café buys a fancy new espresso machine for $10,000. The real cost is much more than that. You have to include all the necessary expenses to get it ready for brewing.

- Purchase Price: The $10,000 paid to the supplier.

- Shipping and Freight: The $500 it cost to get it to your door.

- Installation and Setup: The $300 you paid a pro to install and calibrate it.

- Sales Tax: The $800 in taxes you couldn't avoid.

So, the actual asset cost you'll record isn't $10,000. It's the sum of all these parts: $11,600. This is the number you'll use as your starting point.

Estimating the Useful Life

Next, you have to estimate the asset's useful life. This is simply the period you expect the asset to be productive and generate revenue for your business. The key here is that "useful life" isn't necessarily how long the asset could last. It's about how long it will be practically useful to you.

The espresso machine manufacturer might claim it can last for 15 years. But a smart café owner knows that constant, heavy use means it will probably need replacing in about 7 years to keep the coffee quality high and avoid constant breakdowns. For this business, the useful life is seven years.

An asset's useful life is an estimate based on experience, industry standards, and expected usage patterns. It’s a judgment call, not a hard-and-fast rule, directly impacting the amount of depreciation recorded each year.

Projecting the Salvage Value

Finally, you need to pin down the salvage value, sometimes called residual value. This is your best guess at what the asset will be worth at the end of its useful life. It’s the scrap value or what you think you could sell it for when you're done with it.

After seven years of cranking out lattes, the café owner might figure they can sell the old machine for parts or to a smaller shop for $1,000. That $1,000 is its salvage value. For some assets, the salvage value might be zero if you expect it to be completely obsolete or worn out.

Before you can start calculating, you need to pull these three numbers together. This table breaks them down for our espresso machine example.

| Component | Definition | Example (For a $12,000 Machine) |

|---|---|---|

| Asset Cost | The total expenditure to acquire an asset and prepare it for use. | $11,600 ($10,000 price + $500 shipping + $300 install + $800 tax) |

| Useful Life | The estimated period the asset will be productive for the business. | 7 years (Based on expected usage and replacement cycle) |

| Salvage Value | The estimated resale or scrap value at the end of its useful life. | $1,000 (Expected price for selling the used machine) |

With these three inputs, you're ready to go. The total amount you'll depreciate over the asset's life—the depreciable base—is simply the asset cost minus the salvage value. In this case, it’s $10,600.

Understanding these core components is essential when you're valuing business plant and machinery, as they form the basis for determining an asset's book value over time.

The Three Main Depreciation Methods Explained

Once you’ve nailed down your asset’s cost, useful life, and salvage value, you have to decide how to spread that cost over time. The method you pick isn't just an accounting formality; it dictates the pattern of your expense recognition. Will it be a steady, predictable hit each year, or a larger expense upfront? In accounting, there’s no single “right” way—just different methods suited for different assets and business goals.

The three heavy hitters are the straight-line method, the declining balance method, and the units of production method. Each one tells a slightly different story about how an asset’s value gets used up. Getting to know them is crucial for painting an accurate financial picture of your business.

As you can see, these three inputs—cost, useful life, and salvage value—are the building blocks for calculating the depreciable base. This is the total amount you'll eventually write off as an expense.

The Straight-Line Method

This is the simplest and most popular kid on the block. Think of straight-line depreciation like a flat-rate subscription—you expense the exact same amount, year in and year out. It’s the perfect fit for assets that deliver consistent value over their entire lifespan, like your office furniture or basic machinery.

Its biggest advantage is its simplicity. The math is easy, and it creates a smooth, predictable expense on your income statement, which can help profits look more stable from one year to the next.

The formula is as clean as it gets:

Annual Depreciation Expense = (Asset Cost – Salvage Value) / Useful Life

Let's put it to work. Imagine a marketing agency buys a high-end commercial printer for $25,000. They figure it will last for 5 years and be worth about $2,500 for parts at the end.

Here’s the breakdown:

- Asset Cost: $25,000

- Salvage Value: $2,500

- Useful Life: 5 years

Annual Depreciation Expense = ($25,000 – $2,500) / 5 = $4,500

Using the straight-line method, the agency would book exactly $4,500 in depreciation expense every year for five years. Simple as that.

The Declining Balance Method

If the straight-line method is a steady marathon, the declining balance method is a sprint out of the gate. This is an accelerated depreciation approach, meaning you record much higher expenses in the early years and less as the asset gets older. This lines up perfectly with how many assets actually lose value—think of a new car or a computer that loses a big chunk of its worth the moment you start using it.

This method is ideal for assets that are at their most productive and efficient when they’re brand new. The most common flavor of this is the double-declining balance method, which, as the name suggests, depreciates the asset at twice the straight-line rate.

Here's the formula:

Annual Depreciation Expense = (2 / Useful Life) * Book Value at Beginning of Year

Let’s use our same $25,000 printer with a 5-year life:

- First, find the straight-line rate: 1 / 5 years = 20%

- Next, double it: 20% * 2 = 40%

Now, we apply that 40% rate to the book value each year, which shrinks over time:

- Year 1: 40% * $25,000 = $10,000 (Book value drops to $15,000)

- Year 2: 40% * $15,000 = $6,000 (Book value drops to $9,000)

- Year 3: 40% * $9,000 = $3,600 (Book value drops to $5,400)

One key detail: you ignore the salvage value for the yearly calculation. However, you have to hit the brakes once the book value falls to the salvage value ($2,500 in our case). You can't depreciate an asset below its estimated final worth.

The Units of Production Method

What if an asset’s value has less to do with time and more to do with use? That’s the exact problem the units of production method solves. This approach ties the depreciation expense directly to output—making it a fantastic choice for manufacturing equipment, delivery vehicles, or any machine where value is best measured in units made, miles driven, or hours run.

The expense fluctuates each year based on how much you actually used the asset. This beautifully follows the matching principle: when production is high, revenue is high, and so is the corresponding depreciation expense.

It’s a two-step process:

- Calculate the Depreciation Rate Per Unit: (Asset Cost – Salvage Value) / Total Estimated Production Units

- Calculate Annual Expense: Depreciation Rate Per Unit * Units Produced in the Year

Let's apply this to our $25,000 printer, which is expected to produce 1,000,000 pages over its lifetime.

- Depreciation Rate Per Page = ($25,000 – $2,500) / 1,000,000 pages = $0.0225 per page

Now, the annual expense is just a matter of counting the pages:

- Year 1: 300,000 pages printed * $0.0225 = $6,750

- Year 2: 250,000 pages printed * $0.0225 = $5,625

- Year 3: 150,000 pages printed * $0.0225 = $3,375

As you can see, the expense perfectly mirrors the printer's actual workload each year.

Comparing Depreciation Methods

Each method provides a different lens through which to view an asset's value decline. To make the choice clearer, here’s a side-by-side comparison.

| Method | Basis of Calculation | Expense Pattern | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Straight-Line | Time | Constant and predictable each year | Assets that lose value evenly over time (e.g., office furniture, buildings). |

| Declining Balance | Time (with accelerated rate) | Higher in early years, lower in later years | Assets that are most productive when new (e.g., tech, vehicles). |

| Units of Production | Usage (units, hours, miles) | Varies directly with asset usage | Assets where wear and tear is tied to output (e.g., manufacturing machinery). |

Ultimately, choosing the right method is a strategic decision. The straight-line method offers simplicity, the declining balance method reflects the rapid value loss of certain assets, and the units of production method perfectly aligns costs with revenue-generating activity.

How to Record Depreciation Journal Entries

Running the numbers on depreciation is just the first step. To make it official, you need to get that calculation into your company's books. This happens through a simple but vital transaction called a journal entry.

This entry is how you formally recognize the expense on your financial statements, which in turn impacts your company's reported profit and the value of your assets.

Every time you record depreciation, you'll be working with two specific accounts:

- Depreciation Expense: This is an expense account, so it shows up on your income statement. When you record it, you lower your company's net income for that period.

- Accumulated Depreciation: This is what's known as a contra-asset account. It lives on the balance sheet and is paired directly with the asset it relates to.

So, what exactly is a contra-asset account? Think of it as a negative value that chips away at the asset's original cost over time. Its real genius is that it reduces the asset's book value without you having to touch the original purchase price. This way, you can clearly see both what you paid for the asset and how much of its value has been "used up" so far.

The Standard Depreciation Journal Entry

The good news is that no matter which method you use—straight-line, declining balance, or units of production—the actual journal entry looks the same every single time. It's a fundamental piece of accounting that quickly becomes second nature during your month-end or year-end closing.

Here’s the universal formula:

- You debit the Depreciation Expense account.

- You credit the Accumulated Depreciation account.

In accounting, a debit increases an expense, and a credit increases a contra-asset account. This one entry perfectly captures the expense for the period while also lowering the asset's net value on your balance sheet. To see how these entries flow into the bigger picture, it helps to understand how to prepare a trial balance.

Journal Entry Examples in Action

Let's bring back that $25,000 printer to make this concrete. We'll post the journal entries using the annual depreciation figures we calculated earlier for each method.

Example 1: Straight-Line Method

Under this method, we had a predictable annual expense of $4,500. At the end of the first year, your accountant would record this:

| Account | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|

| Depreciation Expense | $4,500 | |

| Accumulated Depreciation | $4,500 | |

| (To record annual depreciation on printer) |

Example 2: Double-Declining Balance Method

Using this accelerated method, the first-year expense was a much larger $10,000. The structure of the entry is identical, just the numbers change:

| Account | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|

| Depreciation Expense | $10,000 | |

| Accumulated Depreciation | $10,000 | |

| (To record annual depreciation on printer) |

These entries might seem small on their own, but their collective impact is enormous. Just to give you a sense of scale, U.S. corporations in the durable manufacturing sector alone recorded over $400 billion in depreciation in recent years, hitting $412.3 billion in 2021. This just goes to show how profoundly depreciation shapes reported profits and tax strategies across the entire economy. Find more data on corporate depreciation from the Federal Reserve.

Depreciation for Taxes Versus Financial Reporting

If you've ever compared your company's internal financial statements to your tax return, you might have scratched your head. The depreciation numbers rarely match. This isn’t a mistake—it's actually a standard and perfectly legal practice.

The reason is that these two reports serve completely different purposes and play by different rules. Think of it like having two different manuals for your car: one for day-to-day driving and another for passing a strict emissions test. Both are correct, just for different contexts.

Financial Reporting Follows GAAP

When you're preparing financial statements for your own books or for outside investors and lenders, you follow a set of rules called Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). GAAP’s mission is to paint a clear, consistent, and honest picture of your company's financial health.

To do that, methods like the straight-line approach are popular because they spread the cost of an asset evenly over its life. This gives a much smoother and more predictable view of your long-term profitability and asset value. The name of the game here is accuracy and consistency.

Tax Reporting Follows IRS Rules

When it's time to file taxes, you put away the GAAP rulebook and pick up the one from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). The IRS isn't as concerned with perfectly matching an asset's economic wear and tear. Instead, tax laws are often written to encourage businesses to spend money and stimulate the economy.

This is where the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS) comes in. MACRS is the depreciation method required by the IRS for most assets, and it lets you take much bigger deductions in the early years of an asset's life. This accelerated write-off lowers your taxable income right away, reducing your tax bill and freeing up cash.

The core difference is simple: Financial accounting aims to accurately match expenses with the revenue they help generate over time. Tax accounting, on the other hand, is designed to offer incentives for business investment through faster deductions.

Why You Use Two Different Methods

So why juggle two sets of books? It's all about strategy. For your shareholders, you might use the straight-line method to report stable, consistent profits, avoiding the big dips that accelerated depreciation would cause on paper.

At the same time, you’ll use MACRS on your tax return to get the biggest tax break you can, right now. It's a smart way to manage your cash flow. This dual approach allows you to present a steady financial narrative while legally minimizing what you owe Uncle Sam. This is where staying organized with a solid small business tax preparation checklist becomes incredibly helpful.

This strategy is especially powerful in industries with a lot of heavy equipment or property. To see how these depreciation concepts are applied in a real-world investment context, you can explore different real estate investment tax strategies. Ultimately, both methods are the "right" way to do things—one is for transparent financial storytelling, and the other is for smart tax planning.

Beyond the Basics: Real-World Depreciation Scenarios

The basic depreciation methods are a great starting point, but the real world is rarely that simple. Business conditions change, you sell assets, and sometimes your initial estimates just don't pan out. This is where we move beyond the textbook formulas and into the practical side of managing depreciation.

One of the biggest real-world challenges is inflation. We calculate depreciation based on historical cost—what you originally paid for an asset. But what about its replacement cost—what it would take to buy that same asset today? When inflation is high, there can be a huge gap between those two numbers.

This gap can paint a misleading picture of profitability. Your depreciation expense, based on a much lower historical cost, looks small, making your net income look bigger. But in reality, you aren't setting aside nearly enough to cover the true cost of replacing that equipment down the road. A fascinating study on U.S. Steel showed that using replacement cost gave a far more realistic view of the company's financial health than sticking to historical figures. You can see the full research on this topic to dive deeper into how this plays out.

What Happens When You Sell a Depreciated Asset?

It’s common to sell equipment before it's fully depreciated. When you do, you have to figure out if you made a gain or a loss on that sale. The key here is that you’re not comparing the sale price to what you first paid. Instead, you compare it to the asset’s book value at the moment you sell it.

The math is straightforward:

- If Sale Price > Book Value = Gain on Sale

- If Sale Price < Book Value = Loss on Sale

Let’s walk through an example. Say your company sells a machine for $10,000. You originally bought it for $50,000, and over the years, you’ve recorded $42,000 in accumulated depreciation. This means its current book value is $8,000.

Since you sold it for $10,000 (which is more than its $8,000 book value), you’ve got a $2,000 gain on the sale. This gain gets reported as income on your income statement.

Adjusting Your Estimates and Dealing with Impairment

Let’s be honest—our initial estimates aren't always perfect. You might project a machine will last seven years, but with great maintenance, it looks like it will easily last ten. You don't go back and change past financial statements. Instead, you adjust your depreciation prospectively. You'll take the remaining book value and spread it over the new remaining useful life.

A more sudden issue is impairment. An asset becomes impaired when something happens that craters its value, and it can no longer generate the cash you expected. Think about a piece of specialty tech that becomes obsolete overnight because of a new invention.

When an asset is impaired, you can’t just keep depreciating it as if nothing happened. You have to write down its value to its current fair market value and recognize that loss immediately. This keeps your balance sheet from overstating what your company's assets are truly worth.

Getting these advanced scenarios right is critical for accurate financial reporting. It’s a huge part of telling your company's true financial story and a key step in professional year-end closing procedures.

Got Questions About Depreciation? Let's Clear Them Up.

Even after you've got the basics down, a few common questions about depreciation always seem to pop up. Let's tackle some of the most frequent ones to make sure you have a rock-solid understanding of how it all works in the real world.

Can You Depreciate Land in Accounting?

Short answer: nope. Land is the one major asset you can't depreciate.

The reason is simple—land is considered to have an unlimited useful life. Think about it: a building slowly breaks down, a truck wears out, and technology becomes obsolete. Land, on the other hand, doesn't get "used up."

Because it doesn’t lose its value from use, it stays on your balance sheet at its original purchase price. The only time its value might be written down is in the case of a permanent impairment, but that’s a whole different accounting ballgame.

What’s the Difference Between Depreciation and Amortization?

This is a classic. Depreciation and amortization are two sides of the same coin; they both spread an asset's cost over its useful life. The key difference is what kind of asset you're talking about.

- Depreciation is for tangible assets. These are the physical things you can see and touch, like machinery, company vehicles, and office furniture.

- Amortization is for intangible assets. These are valuable items that aren't physical, like patents, copyrights, and trademarks.

So, you'd depreciate the new 3D printer in your workshop, but you'd amortize the patent for the groundbreaking technology inside it.

While the mechanics are similar, getting this right is non-negotiable for accurate financial reporting. Mixing them up can give a misleading picture of what a company truly owns.

What Happens When an Asset Is Fully Depreciated?

Once an asset is fully depreciated, its book value has been written down to whatever you decided its salvage value was. From that point on, you stop recording any more depreciation expense for it.

But here's a key point: even if the asset is still chugging along and making you money, you can't depreciate it anymore.

The asset’s original cost and its total accumulated depreciation will both stay on your balance sheet, showing that you still own and use it. It's only when you finally sell or scrap the asset that you'll make a final journal entry to remove both accounts from your books.

Keeping your financial data in order is crucial. Bank Statement Convert PDF is a great tool for converting messy PDF bank statements into clean Excel spreadsheets, saving you a ton of time and preventing errors. Learn more and streamline your accounting process today.